Why the Water Supply Needs a Splash of Competition

Australia’s inefficient water monopoly structure is gouging consumers. It is protected by state legislation and bureaucrats with little appetite for change. What’s needed is a radical overhaul of the business philosophy underpinning water services, to allow improved technology and community-led alternatives to cut water costs.

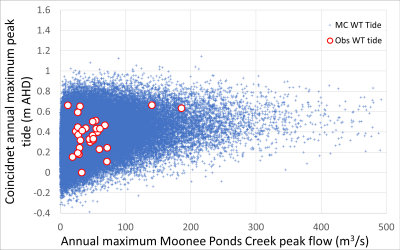

The millennium drought highlighted how innovative ways to increase local supply and reduce demand for grid water could improve the efficiency of the whole system. Simple strategies such as rainwater tanks and reduced consumption ensured that many Australian cities did not run out of water.

Those lessons have been quickly forgotten. Centralised supply through water grids and expensive desalination plants are now seen as the only economically viable solutions for Australian cities.

A need for security is a status quo argument of centralised monopoly solutions for essential infrastructure. The Australian Financial Review (Editorial: Taxpayers left Holding the Desalination Bag) highlighted that claims of extreme weather have driven demand for expensive desalination plants in preference to dams. However, desalination plants in Victoria and New South Wales, and a water grid in Queensland have left multi-billion dollar debts. Australian households are paying the costs.

Why is this happening? We need to understand the economic and political drivers of these outcomes to fully appreciate what’s causing this market failure.

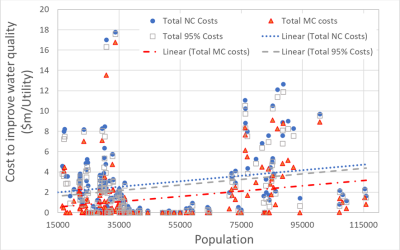

The economic efficiency of Australia’s centralised water utilities is rapidly declining – and consumers are paying for it. At a macroeconomic level (household welfare across the economy), grid water costs of households in Melbourne, Adelaide and South East Queensland have jumped by up to 180 per cent over the past decade, while water usage has increased by less than 10 per cent. At a microeconomic level (Utility budgets), the operating costs for water utilities have soared by up to 170 per cent and the economic efficiency of water supply has plunged by up to 2300 per cent.

The results for Perth are a little better in response to limited diversification of supply and increased water conservation. Residential water demand has increased by 22% and total demand has increased by 12% over the last decade. Water operating costs have risen by over 76% and total costs have increased by at least 110%. The grid water costs paid by Perth households has increased by 102%. Economic efficiency has declined by 500% to 910%.

In contrast, Sydney’s water supply is far more economically efficient. Household spending on grid water and utility operating costs increased by just 18 to 54 per cent over the past decade, for a 10 per cent increase in usage. This translates to a fall in economic efficiency of less than 540 per cent, just 22 per cent of the drop in Melbourne, Adelaide and South East Queensland.

The reason for Sydney’s better performance is simple: competition. Local water sources and demand management provided by the BASIX legislation, and a desalination plant paid for by government funds generated better outcomes for households, including increased disposable income. It sounds counter-intuitive, but competition from local water supplies and reduced water demand also generates better outcomes for water utilities. This is because reductions in costs – particularly for grid security infrastructure – are many times greater than loss of revenue.

At present, many water utilities are locked in a vicious cycle of trying to spend their way out of infrastructure-induced debt by increasing water prices and consumption to generate more revenue. Desalination and water grids are also seen to maximize market share for grid water. This process dominates water industry balance sheets, leaving negligible funds for innovation and viable alternatives. Increasing water consumption to boost revenue within a centralised monopoly structure means costs go up more than the additional revenue – ultimately driving higher prices and greater debt. At the same time, fixed tariffs mean that consumers have no incentive to reduce water demand.

The political drivers of this market failure are as much to blame as the economic drivers outlined above. State bureaucracies own the water monopolies, oversee the regulators, recommend executive appointments and decide membership of consultant panels. This arrangement funnels substantial funds to State budgets and to research and industry associations, with minimal democratic oversight.

What’s needed is more competition, as well as independent regulation and advice, to develop alternatives to water grids and desalination plants and to cut everyone’s water bills. This can be achieved by deregulation of the water industry to clearly separate state government ownership from regulation and governance of water utilities. State water bureaucracies should permit access of competing solutions or businesses to the market.

Implementation of full variable tariffs (no fixed charges) will finally send the necessary price signals to the also deregulated market – driving market responses from business and consumers. There is also a need for more independent and responsive governance of water utilities by including a majority of democratically elected representatives on water utility boards. Perhaps some federal oversight is needed.

Article in the Australian Financial Review on 19 January 2017 by Professor P J Coombes with comments from Michael Smit and Dr Katherine Daniell.