The politics of introducing innovation in multiple level governance systems

A good idea with clear benefits, potential to mitigate impacts of an external crisis (for example: drought and uncertainty about security of water supplies) and a meeting with the Minister or Department – success? This Blog is an extract of the Key Note Presentation to the Rotomound 2014 Conference at Coogee in New South Wales and a snapshot of a soon to be released series of multimedia publications derived from over 120 innovative projects and up to 20 significant policy processes.

It should be a relatively easy thing to achieve influence with Government when the benefits of a decision are so obvious, but is that how Government really works? A range of case studies provide some insight into behaviours experienced in the process of introducing innovations in the water sector. This discussion uses selected case studies to highlight some of the real influencers, identifies the behaviour of the various actors in the drama and provides some understanding the sometimes difficult journey of apparently simple policy decisions.

Figtree Place in Newcastle

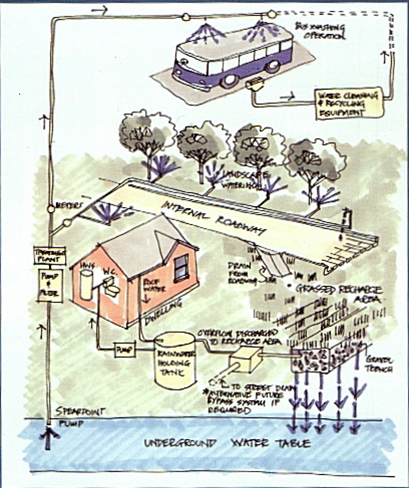

The Figtree Place project is an urban redevelopment of the Newcastle bus station that responded to concerns about the drought in the 1990s. The proponents of the project were Newcastle City Council, the NSW Department of Housing, the Office of Community Housing and the Federal Government Building Better Cities program. The project enjoyed conditional support from the Department of Health and EPA, and encountered resistance from the Water Authority and plumbers. The Figtree Place project is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Figtree Place redevelopment

The innovations in the project included:

- Rainwater collected in four rainwater tanks for hot water and toilet flushing in all units.

- Stormwater runoff from internal roads, paths and overflow from rainwater tanks directed to the aquifer via soak pits.

- Ground water extracted from the aquifer is used for domestic irrigation and bus washing.

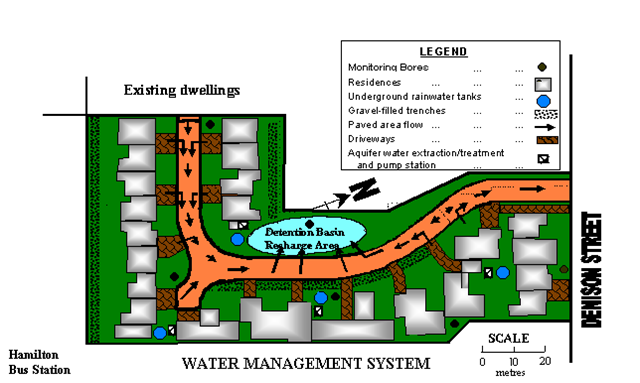

An overview of the innovative elements of the Figtree Place project are provided in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Overview of the innovative water cycle strategy

Figure 3: plan view of the Figtree Place project

The observed performance of the Figtree Place project was:

- 45% reduction in mains water use in units resulting from use of rainwater for hot water and flushing toilets

- 60% reduction in mains water use for the entire site (rainwater and stormwater harvesting)

- 1% saving in construction costs ($950/unit)

- Total annual cost savings of $4,038 ($150/unit)

- No stormwater runoff from the site with restoration of natural infiltration to the aquifer, and

- Rain water used in hot water systems set at >50°C was compliant with Australia drinking water standards

Although the project provided clear benefits, concerns from the Water Authority, Health Department and Consultants provided substantial uncertainty. Indeed, an overview of the processes to develop and operate the project provide insights into the battle to accept an innovative strategy. Newcastle Council and University of South Australia (John Argue) provided counter arguments in favour of the project in the context of community concern about drought and impacts of urban development on the environment.

Newcastle Council was granted funding from NSW Stormwater Trust and Federal Government Building Better Cities to develop the project. The external funding was a catalyst for project approval resulting in partnership between the proponents and resisting stakeholders to build and monitor the performance of the project. The monitoring project revealed that the Water Authority, Construction Company and plumbers changed the design during construction under supervision by NSW Housing Department.

This resulted in many construction errors and including the discovery that the alternative water sources were not connected. Further investigation revealed that some individuals in the Water Authority, Council and construction company believed that “project will not work” and should note be constructed as designed. Nevertheless, the University of Newcastle (including the author) and Housing Department led a correction of the design elements of the project with agreement from all stakeholders.

Following correction of some of the construction issues, the innovative project operated very well during the period of supervision by University of Newcastle. Ultimately, the housing company and Water authority closes project for “perceived health concerns resulting from selected water quality samples” after University supervision ends. It is noteworthy that the monitoring results from University of Newcastle (see Rainwater Tanks Revisited, New Opportunities of Integrated Water Cycle Management) revealed a treatment train for rainwater and stormwater harvesting.

Initiation of State Environmental Policies for Sustainable Buildings in Sydney

The push for inclusion of sustainable buildings was driven by concerns about the security of water supplies and the impacts of urban development on the environment. Early efforts to include sustainable buildings was championed by environment groups, local government and prominent individuals such as Michael Mobbs. The environments groups commissioned independent analysis which was submitted to the NSW Cabinet. The proposal was cautiously supported by the Water Minister and Premier.

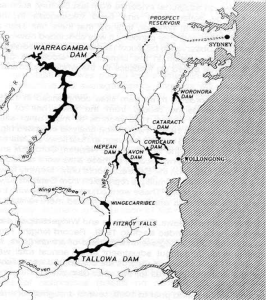

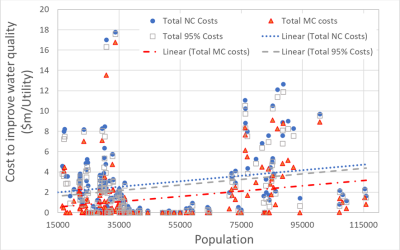

The Water Authority, Departments of Health and Public Works opposed the idea. An overview of the resisting arguments was that small local solutions do not work and only large scale strategies provide benefits. It was also claimed that rainwater harvesting to dangerous and unreliable. An overview of the water supply system for Greater Sydney is provided in Figure 4 and the impacts of various building scale strategies is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Overview of the water supply system for Greater Sydney

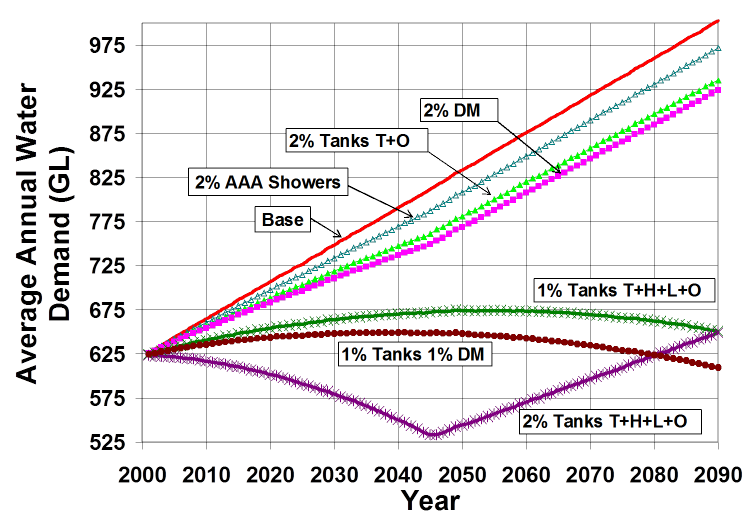

Figure 5: Average annual water demands from various building scale options for Greater Sydney.

Figure 5 shows that building scale options were shown to have the potential to significantly reduce Sydney’s future water demands. Note that following descriptions relate to the options:

-

Tanks denote 3,000 litre rainwater storages,

-

DM is full suite of water efficient appliances and behaviours,

- 1% or 2% indicates the proportion of buildings in any year that adopt the strategy

- T is toilet, H is hot water, L is laundry and O is outdoor uses

- AAA shower indicates a low flow shower

The Systems Analysis also included a range of environmental criteria as follows:

- Streamflow in the Shoalhaven River as a proportion of natural streamflow remaining in January 2020

- Frequent stormwater discharges as indicated by reduced peak discharges for 3 month ARI

- Average annual reduction in volumes created by demand management measures

- Reduced energy consumption

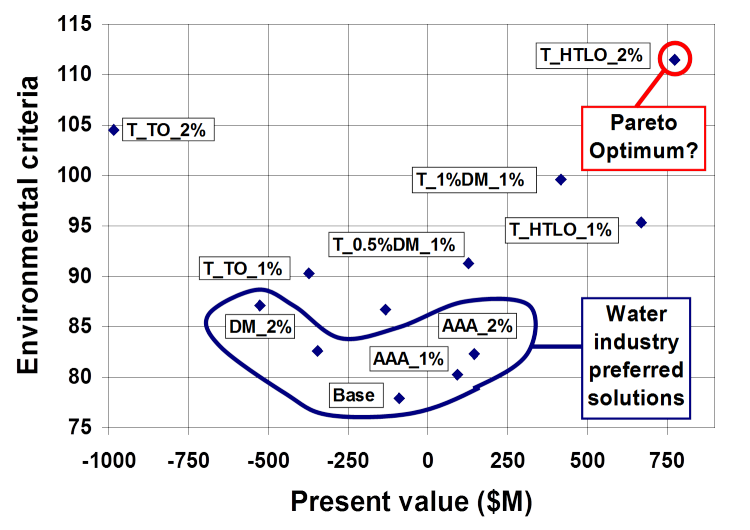

The Systems Framework for Greater Sydney allowed a combination of environmental and investment criteria in a Pareto Diagram. This process provided clarity on potential of the Options as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Pareto Diagram of the building scale Options for Greater Sydney (circa 1999).

The analysis revealed clear benefits as shown in the Pareto Diagram. The Water Minister supported the Systems Analysis sponsored by Environment group and investigation of policy options by various departments. However, the Water Authority, Department of Health and others hold seminars and workshops to highlight danger of using rainwater. Indeed, there was action to ban use of rainwater throughout NSW and the Environment groups were dependent on the Water Authority for funds which impacted on the independence of the process.

The workshops about the danger posed by rainwater invokes responses from community and local government throughout the state of New South Wales. In particular, a group of Mayors of regional councils expressed concern that local government cannot afford to built additional infrastructure to replace existing rainwater supplies and access other water resources. A submission from local government to the Premier resulted in a clarifying statement from the Premier “ the NSW government permits all uses of rainwater” and “Department of Health can only provide advice on the use of rainwater”

The Department of Planning was charged with implementing Sydney BASIX policy which ultimately involved collaboration with the Water Authority and Department of Health.

Extension of the BASIX State Environmental Planning Policy to regional New South Wales

A New Water Minister and Department of Energy and Utilities aimed to extend the BASIX policy to regional NSW. They commissioned independent analysis. Similar to the Sydney process, the policy was opposed by some Water Authorities, and Departments of Public Works and Health. It was claimed that rainwater harvesting did not provide benefits and was dangerous. However, rainwater harvesting was supported by community and local government. Indeed, rainwater was safely utilised as a sole source of water by over 3 million Australians and seminal epidemiological studies by Heyworth revealed that drinking rainwater did not pose additional health risks when compared to mains water.

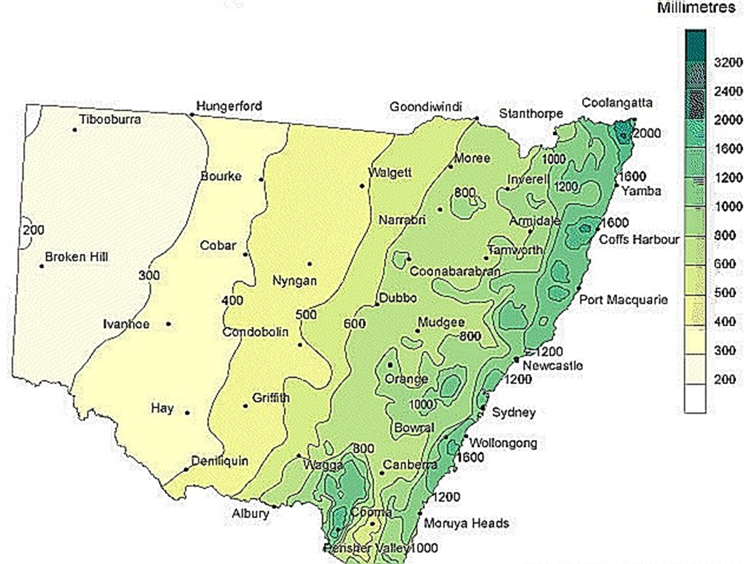

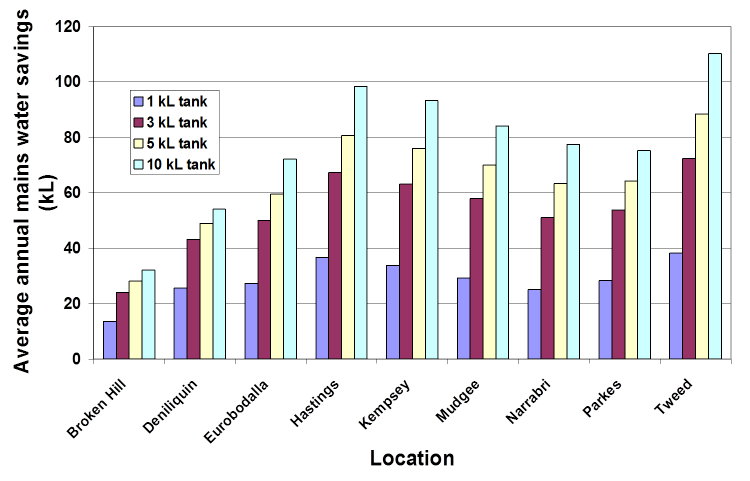

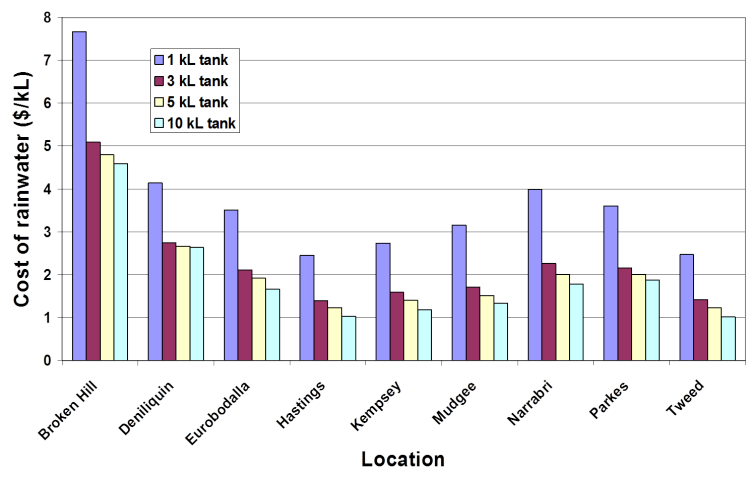

Again the Department of Planning implemented the policy in collaboration with Water Authorities and multiple government agencies. Importantly, the formalisation of rainwater harvesting as part of sustainable buildings as part of the BASIX policy allowed improved design and management outcomes resulting from the creation of new market forces. Overviews of the regional analysis are presented in Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Figure 7: Map of New South Wales with average annual rainfall depths (Australian BOM circa 2004)

Figure 8: Average annual rainwater supply throughout NSW

Figure 9: Building scale “cost” of rainwater supply throughout NSW

Figure 10: Net present value of benefits to Water Authorities from rainwater harvesting

Observations: hidden challenges

A good idea and community support may not be sufficient to foster adoption of a new innovation. Innovations can be seen as challenging existing ideas and governance systems which can involve a battle for control by someone. It is often the case that individuals throughout multi-level governance structures act as gatekeepers to data and information. It is important to realise that more comprehensive information and knowledge about existing related processes is often required to understand the benefits of new innovations. This process can also limit discussions about an innovation to existing considerations that are remote from the potential of a new innovation.

Observations: conditions for success

Successful implementation of a new innovation requires clear messaging and branding about the innovation. The conditions for success are further enhanced by provision of strong evidence of the benefits of the new innovation with supporting decision support processes. Developing champions at two different levels of government with capacity for implementation in one of the levels of government has been shown to be driver of innovation uptake.

The proponents of innovation must recognise competing strategies and incorporate approaches to mitigate the impacts of alternative strategies. It is essential to develop coalitions of support and to ensure that supporters are combined in their understanding of the new innovation.

It is important to plan to incorporate a new innovation into existing governance systems or to succinctly outline any proposed modernisation of governance systems that may be needed to facilitate a new innovation.

Many innovations result from external drivers or crisis – such as floods. Additionally, incentives and funding mechanisms (such as government subsidies) can also lead to the development of new ideas. It is essential that the fate of a new innovation is considered in the absence of external drivers, incentives and funding mechanisms. What is the plan for a new innovation when a drought ends or government subsidies cease?